Native American Celebrities, Games & Other Web Resources

Native American Online Resources

Credit Above 2 Photos: Melbourne Spurr, and Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Designed by Charles R. Chickering, based on a photograph furnished to the Post Office Department by the Washington Star., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Native American Celebrities, Games & Other Web Resources

Native American Online Resources

Credit Above 2 Photos: Melbourne Spurr, and Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Designed by Charles R. Chickering, based on a photograph furnished to the Post Office Department by the Washington Star., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Crazy Crow Trading Post offers this list of Native American Celebrities, Games & Other Web Resources related links to help you in your search for information about American Indian tribes, associations, history and related information. Inclusion in this list does not represent an endorsement by Crazy Crow, although we do try to be selective – and reserve the right to do so.

Games from the Aboriginal People of North America

Around the world people have passed on games as part of their culture. Both children and adults played games in all Aboriginal nations, and because most relied on symbols, these games could be played among different nations who didn’t speak the same language. Many of these games were played for entertainment, but they usually had a religious meaning or were used as learning tools. Each game is presented in a format that includes its origin & history, rules, photos/diagrams, etc. Games presented represent a very varied tribal representation.

American Indian actors, singers and other celebrities. For fans and professionals. Casting, photos, bios, movies, TV, info.

Dewey Beard or Wasú Máza | Minneconjou Lakota | Little Big Horn & Wounded Knee

Dewey Beard or Wasú Máza (“Iron Hail”, 1858–1955) was a Minneconjou Lakota who fought in the Battle of Little Bighorn as a teenager.[1] After Custer’s defeat, Wasu Maza followed Sitting Bull into exile in Canada and then back to South Dakota where he lived on the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation. [2]

Iron Hail joined the Ghost Dance movement and was in Spotted Elk’s band along with his parents, siblings, wife and child. He and his family left the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation on December 23, 1890 with Spotted Elk and approximately 300 other Miniconjou and 38 Hunkpapa Lakota on a winter trek to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation to avoid the perceived trouble which was anticipated in the wake of Sitting Bull’s murder at Standing Rock Indian Reservation. He and his family at the Wounded Knee Massacre, where he was shot three times, and some of his family, including his mother, father, wife and infant child were killed. His experiences were recounted in an in depth interview with Eli S. Ricker (Union Civil War veteran well known for his progressive views on Native Americans) for a book Ricker planned to write.[11] Ricker conducted more than fifty interviews with various Native Americans, as well as scouts and settlers, recording various eyewitness accounts on events during the Indian Wars in the west, such as the Battle of the Little Bighorn and the Wounded Knee Massacre.

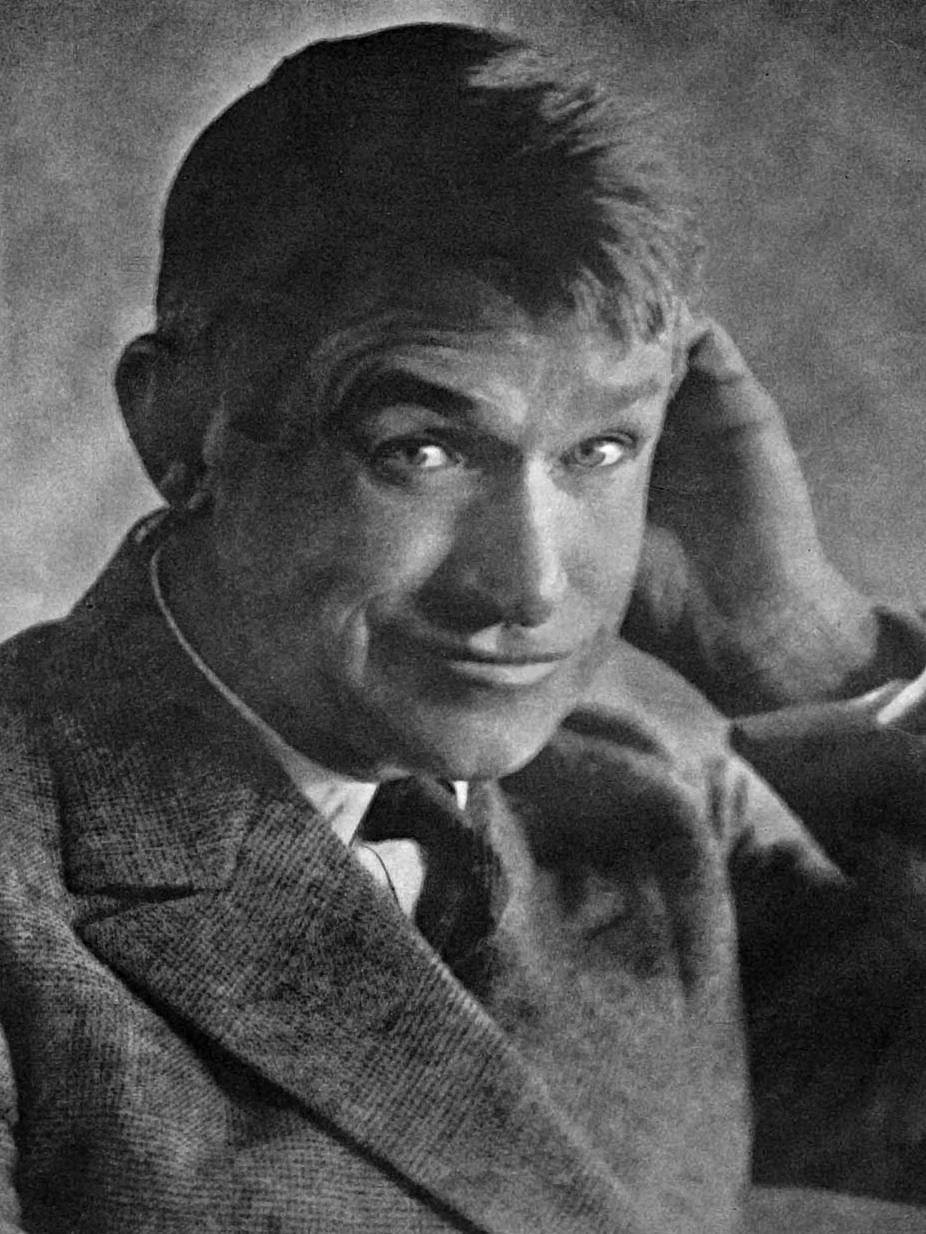

Will Rogers | Cherokee Nation Citizen

William Penn Adair Rogers (November 4, 1879 – August 15, 1935) was an American vaudeville performer, actor, and humorous social commentator. He was born as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, in the Indian Territory (now part of Oklahoma), and is known as “Oklahoma’s Favorite Son”.[1] As an entertainer and humorist, he traveled around the world three times, made 71 films (50 silent films and 21 “talkies”), and wrote more than 4,000 nationally syndicated newspaper columns.[2] By the mid-1930s, Rogers was hugely popular in the United States for his leading political wit and was the highest paid of Hollywood film stars. He died in 1935 with aviator Wiley Post when their small airplane crashed in northern Alaska.[3]

Rogers was born on his parents’ Dog Iron Ranch in the Cherokee Nation of Indian Territory, near present-day Oologah, Oklahoma, now in Rogers County, named in honor of his father, Clem Vann Rogers. The house in which he was born had been built in 1875 and was known as the “White House on the Verdigris River”.[4] His parents, Clement Vann Rogers (1839–1911) and Mary America Schrimsher (1838–1890), were both of mixed race and Cherokee ancestry, and identified as Cherokee.[5] Rogers quipped that his ancestors did not come over on the Mayflower, but they “met the boat”.[6] His mother was one quarter-Cherokee and born into the Paint Clan.[7]

Credit Above Photo: Office of the California Governor, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Click image to enlarge.

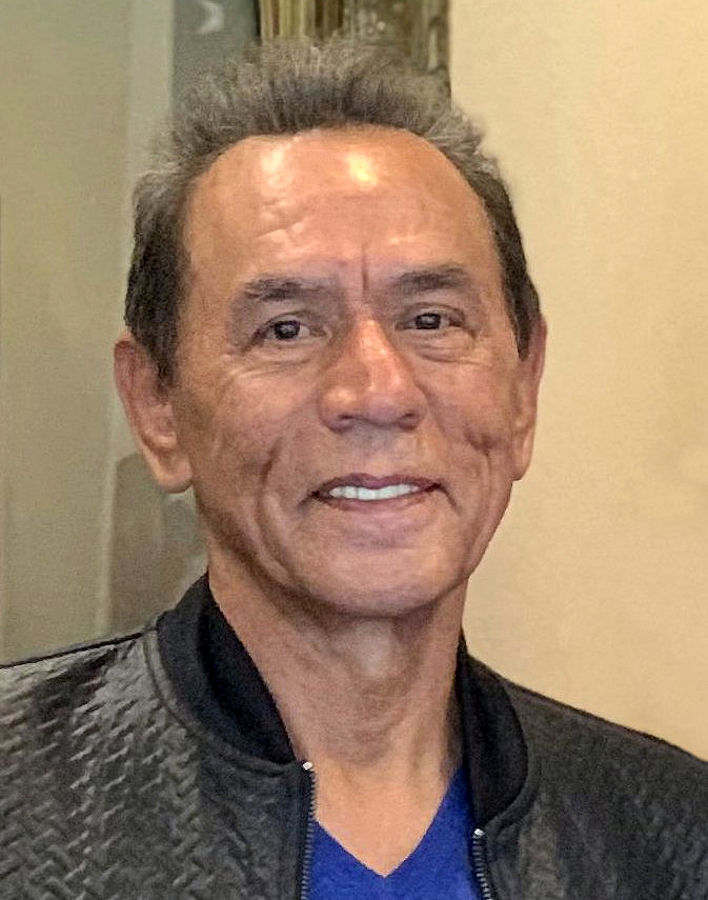

Wes Studi | Cherokee Nation | Actor

Wesley Studi (Cherokee: born December 17, 1947) is a Native American (Cherokee Nation) actor and film producer. He has garnered critical acclaim and awards throughout his career, particularly for his portrayal of Native Americans in film.[15][16] He has appeared in Academy Award-winning films, such as Dances with Wolves (1990) and The Last of the Mohicans (1992), and in the Academy Award-nominated films Geronimo: An American Legend (1993) and The New World (2005). He is also known for portraying Sagat in Street Fighter (1994). In 2019, he received an Academy Honorary Award,[17] becoming the first Native American and the second Indigenous person from North America to be honored by the Academy (the first was Buffy Sainte-Marie). In December 2020, The New York Times ranked him #19 in its list of the “25 Greatest Actors of the 21st Century (So Far),” noting “Wes Studi has one of the screen’s most arresting faces — jutting and creased and anchored with the kind of penetrating eyes that insist you match their gaze.

Studi was born in a Cherokee family in Nofire Hollow, Oklahoma, a rural area in Cherokee County named after his mother’s family.[19] He is the son of Maggie Studie, a housekeeper, and Andy Studie, a ranch hand. Until he attended elementary school, he spoke only Cherokee at home.[20] He attended Chilocco Indian Agricultural School for high school and graduated in 1964; his vocational major was in dry cleaning.[8]

REFERENCES CITED

- 1Curtis, Gene (June 5, 2007). “Only in Oklahoma: Rogers statue unveiling filled U.S. Capitol”. Tulsa World. Archived from the original on December 10, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- 2Schlachtenhaufen, Mark (May 31, 2007). “Will Rogers grandson carries on tradition of family service”. OkInsider.com. Oklahoma Publishing Company. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- 3Video: Man of the Year 1935: Will Rogers. Man of the Year (TV Show). 1945. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- 4“RSU and Will Rogers Museum to Discuss Possible Merger” (Press release). Rogers State University. April 18, 2007. Archived from

- 5Ben Yagoda (2000). Will Rogers: A Biography. p. 8. ISBN 9780806132389.

- 6“Adventure Marked Life of Humorist”. The New York Times. August 17, 1935. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- 7Carter, Joseph H. and Larry Gatlin. The Quotable Will Rogers. Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith, Publisher, 2005:20.

- 8Lamparski, Richard (1982). Whatever Became Of …? Eighth Series. New York: Crown Publishers. pp. 106–07. ISBN 0-517-54855-0.

- 9“Eli Ricker interviews Wounded Knee survivors”. Nebraska State Historical Society. 2004-03-29. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- 10Illustrated history of Nebraska: Volume 3 By Julius Sterling Morton p. 555

- 11Give me eighty men: women and the myth of the Fetterman Fight By Shannon D. Smith p. 172 Publisher: University of Nebraska Press (June 1, 2008) Language: English ISBN 0-8032-1541-X

- 12Dewey Beard, Wikipedia online resourse. Accessed April 11, 2023.

- 13Eli S. Ricker, Wikipedia online resourse. Accessed April 11, 2023.

- 14Wes Studi, Wikipedia online resourse. Accessed April 12, 2023.

- 15Galbraith, Jane (December 14, 1993). “Q&a with Wes Studi: ‘I Came Into the Business at the Right Time'”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- 16Carter, Kevin (December 22, 1993). “Actor Champions Indian Heritage”. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- 17Hammond, Pete (June 3, 2019). “Oscars: Governors Awards To Geena Davis, David Lynch, Wes Studi, Lina Wertmuller”. Deadline Hollywood.

- 18“Wes Studi: ‘A True Warrior'”. U.S. Veterans and Military magazine. August 16, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- 19Native Networks. Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

- 20Beale, Lewis (December 16, 1993). “Wes (‘Geronimo’) Studi Wary of Political Correctness”. New York Daily News. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- 21“The Chilocco Annual, 1964” (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration.

- 22Currey, R. (March 14, 2015). “Wes Studi: at the edge of courage”. VVA Veteran. Vietnam Veterans of America. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- 23Eaton, Kristin; Dean, Anna Holton. “The Road to Fame: Wes Studi”. Tulsa People. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

Native American Online Resources

Current Crow Calls Sale

March – April

SAVE 10%-25% on popular powwow, rendezvous, historic reenactor, bead & leather crafter supplies. Save on many of our most popular items such as Colonial Clothing: Waistcoats, Knee Breeches & Frockcoat, Missouri River Deluxe Hunting Bags, Readymade Drumsticks, Powwow Drums, Hand Drum Kits, Smoked Color Buckskin, Bison Leather, Trekker Boots and other Colonial Shoes for men and women, Jingles & Lids, Stainless Steel Blades with Guards, Polished Steer Horns, Oval Chevron Beads, Lance Heads, River Cane Flute, Plains Hard Sole Moccasin Kits, Southwest Shoulder Bags, Traditional Serapes, Beaded Cinch Top Bag, Beaded Backpack & more!.